Design of Pomegranate House

Plot Area: 2068 m2

Construction Area: 580 m2 (430 m2 +150 m2)

Year: 2020

Location: Foça, İzmir / Türkiye

Coordinates: 38.641557N, 26.826389E (JRRG+JG)

Climate: Mediteranian (Due to Köppen-Geiger: Csa)

Contractor: Ziynet Özçelik & Mete Özçelik

Consultant: LAB Architects (www.labmimarlik.com)

Architectural Project: Buğra Tetik (Architect – METU)

Statical Project: Ömür Özger (Civil Engineer – METU)

Mechanical Project: Güniz Gacaner (Mechanical Engineer – DEÜ)

Electrical Project: Semih Uçak (Electrical Engineer)

Landscape Project: Münire Sağat (Landscape Architect) & Barış Ekmekçi (Landscape Architect)

Landscape Contractor: Ayten Haytabey (Landscape Architect)

Photos: Şerife Tokay, Deniz Tokay, Buğra Tetik, Ziynet Özçelik, Efe Dağıstanlı, Elif Tokay

Location

Pomegranate House, built with masonry stone and timber frame structure, is located in Foçaköy, 60km northwest of Izmir and 7km from the center of Old Foça. The triangular-shaped plot on the slope of a hill has a wide view of the Gediz River, the Gediz Delta, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Gulf of Izmir extending to the opposite shore.

Needs

Pomegranate House is primarily designed for the residents who form a large family to live at different times or simultaneously throughout the year. In addition, it is intended to be a venue for different activities such as trainings, workshops, and interviews, and to embrace variable guests throughout the year.

Passive House

The main priority of the building, which is requested to be constructed of stone and wood, is to be energy efficient and respectful to the environment. Accordingly, passive design principles and strategies such as orientation, form, space planning, building envelope, shading, thermal mass-supported passive solar heating, natural ventilation, night cooling, natural lighting, and rainwater harvesting were used in the design to reduce energy demand. In addition, efficient active systems such as water treatment systems, grey water recovery, solar water heater, photovoltaic panels, air source hybrid heat pumps, and underfloor heating are also part of the design to reduce consumption. Thanks to these features, Pomegranate House, which minimizes energy needs and produces renewable energy, is at the level of the passive house within the framework of the criteria determined by The Passive House Institute (PHI).

Settlement

Being environmentally friendly, non-green areas were selected to place the house and to use hard landscape. In other parts, the existing fertile soil, plants, and large rocks were preserved as a natural part of the landscape. Despite the 18-metre difference in elevation and 33% slope, retaining walls were not constructed for leveling. The natural terraces of the land were supported against landslides with rocks collected from the plot. Compared to the reinforced concrete retaining wall, rock embankments are an ecological and economical solution with a low carbon footprint as a natural landscape element.

The pomegranate house has no boundry walls. In addition to rocks and landscaping, privacy is provided naturally by the elevation difference from the road in the south and east directions. In the other directions where there are neighbors, only natural landscape elements are used. In addition to being eco-friendly and economic, this approach also supports the idea to provide integration between the house and its environment. [1]

It also pursues visual harmony with the surroundings. For example, the roof of the house creates a harmonious silhouette with the mountains to the west.

The house doesn’t try to stand out, it tries to be a part of nature. This attitude is also reflected in the landscape. The location and height of the house within the land allows the neighbor on the upper plot to benefit from the sun and the view uninterruptedly, just like the pomegranate house.

The positioning of the house respects not only the neighbors’ access to the landscape, wind and sun, but also the surrounding ecosystem and living creatures. Beyond the diversity of plants in the garden, it can be observed that it is home to many creatures, especially ladybugs, butterflies, bees and cats. If the man-made landscape destroys the creatures associated with life there and drives them away from the area, this contradicts the dream of a life close to nature. For this reason, Nar house aims to protect, enrich, contribute to the flow and development of nature in its garden, instead of preventing nature and producing the landscape by human hands.

Orientation

The long side of the rectangular Pomegranate House is orientated exactly to the south.[2] In the plan organization, the main spaces are located in the south.

Large windows framing the southern view also embrace the sun. The roof eaves, balconies and terrace pergola, which are calculated according to different sun angles in summer and winter, are passive elements that provide solar control. In this way, in winter the sun filters deep into the interior, while in summer it is blocked outside the windows. This benefit is reinforced by the different types of glazing used in the south compared to other directions.

Natural Ventilation and Lighting

The facade openings are designed to provide natural ventilation with the breeze coming from the northwest on the east and west facades. Taking into account the difficulty of solar control for heating and cooling in these directions, the windows are of optimum size.

There is a fireplace chimney on the east wall of the house. In the north, the day floor of the house is buried in the ground, while the night floor has openings that support natural lighting. Depending on the time of day, the main spaces of the house are bathed in yellow, blue, red and earth colored natural light.

The windows have louvers hidden between the panes to provide privacy and additional solar control when needed.

To bring the generous view of the Aegean into the house, windows in different directions frame different natural elements, creating the feeling of a painting on the wall. Paintings that change color and composition throughout the day.

Thermal Comfort

As a result of the masonry stone construction, an insulated shell with high thermal mass was achieved in Pomegranate House, contrary to the common approach in modern literature for the Mediterranean climate. Considering the thermal harmony between the floors, the same thermal resistance value was provided in the timber frame walls of the upper floor. In this way, the coolness and warmth inside can be maintained for long periods of time.

Night cooling, which is applied by utilizing day and night temperature differences, contributes to natural cooling in summer, especially on days when there is no wind required for natural ventilation. Apart from natural cooling supported by shading, no additional mechanical system is used for air conditioning. In winter (when the indoor-outdoor temperature difference reaches 22 degrees Celsius), the interior space, which is heated by the sun and the thermal mass of the preferred materials during the day, loses an average of 1 °C of heat during the night. This loss is compensated by the sun during the day. This means that mechanical heating is only needed for a short period of the year.

When selecting materials for the Pomegranate House, their availability in the proximity was taken into consideration to reduce carbon emissions from transportation. In addition, materials with low VOC (volatile organic compound) values were preferred to support indoor air quality.

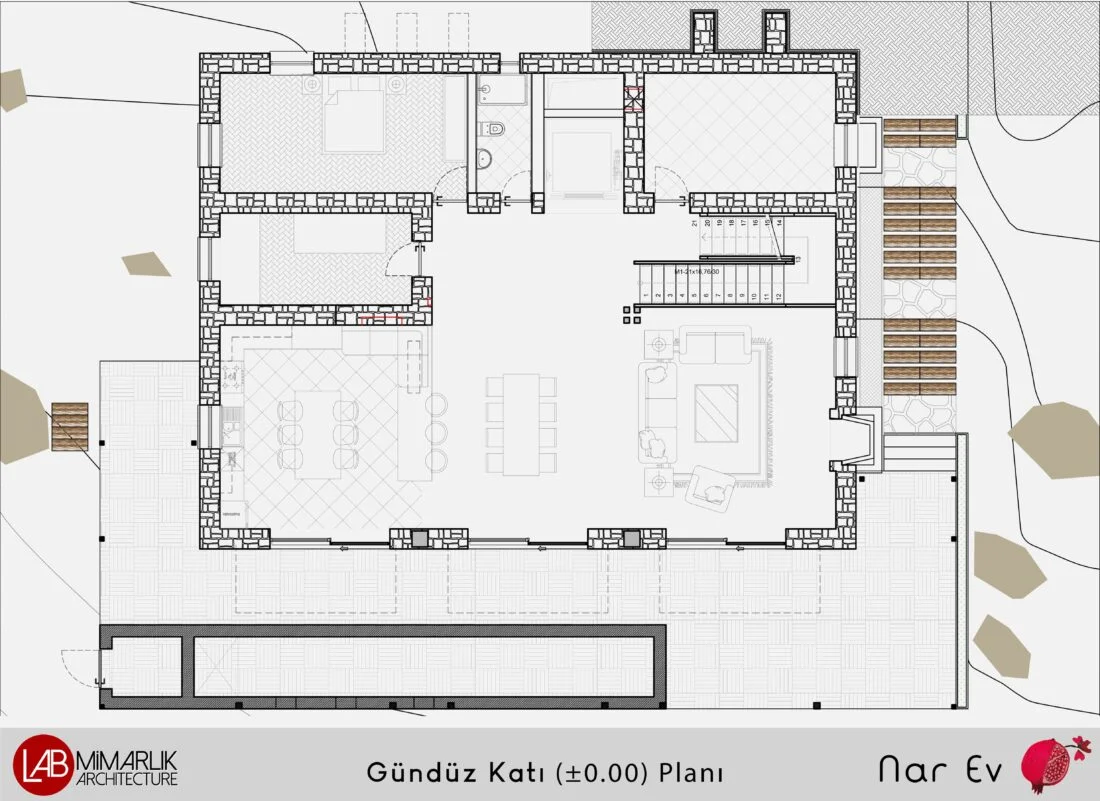

Plan Organisation

On the daytime floor of the Pomegranate House, there is a large living area open to the south that integrates with the open kitchen. In this large living room, there are defined small units; a bookcase under the staircase, a sitting group around the fireplace in the eastern part, a dining table section between the living and kitchen in the middle section and a day hall in front of the staircase that integrates with this section, and finally the kitchen section starting with the kitchen sofa in the west.

The living area adapts to different functions with the movement of the furniture. This spacious living area is combined with the large terrace thanks to the windows opening to the south, making it both more spacious and providing an indoor/outdoor alternative when needed.

Semi-private units such as the kitchen sofa and the bookcase under the stairs enrich the space. These areas, which are not separated by walls, are defined by furniture or architectural elements. In this way, it becomes possible to work in the bookcase under the stairs, lie on the kitchen or library sofa, read the newspaper in the living area, play backgammon in front of the window, and produce in the kitchen without completely breaking away from the daily life sharing of the house.

The request to be a place for different activities such as education, workshops and conversations beyond the lives of the residents made it necessary for the use of the space to be transformable. The section with the seating group can be transformed from a seating area to a cinema or presentation area. The seating area and the center section can be combined with the terrace to host a pilates event. It is possible to diversify this transformability. This main common space is connected to two stone rooms that can be used as guest rooms and can support the main space when needed.

In addition to this, there are service volumes including a lift, a wet room, a cellar and a technical room in the section buried in the ground in the north. There is a cistern under the terrace where rainwater is collected.

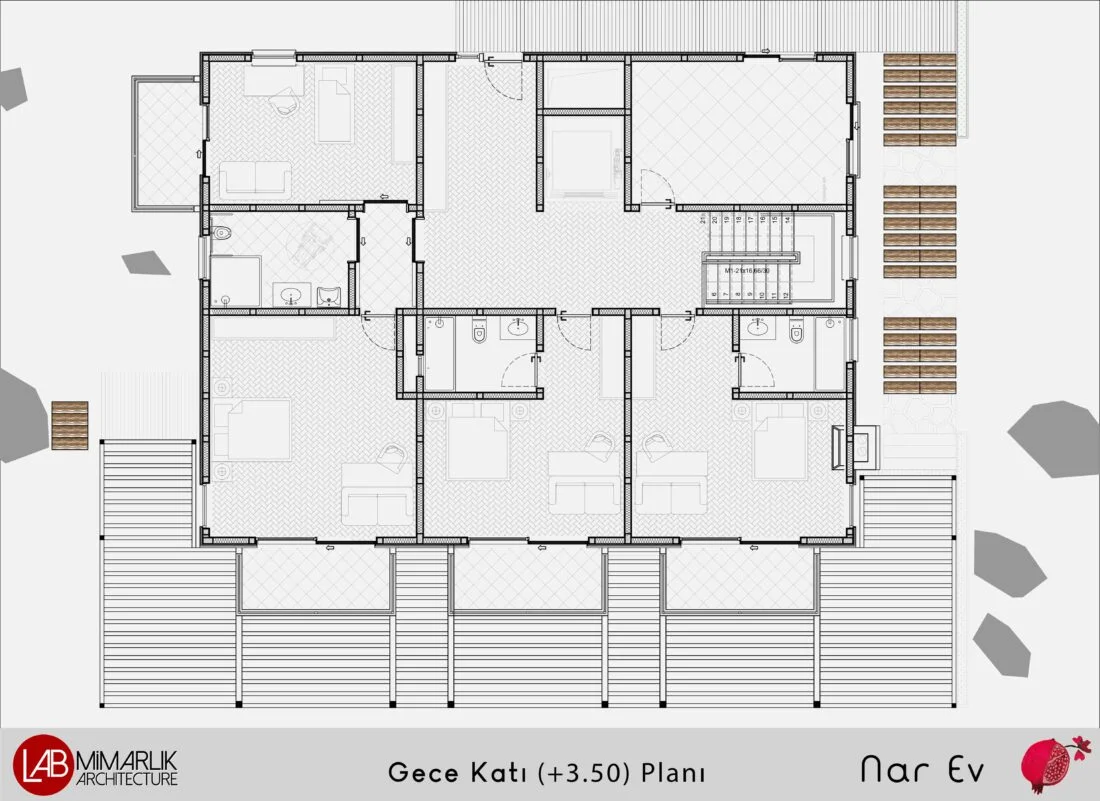

The night floor consists of a night hall, 4 bedrooms with their own wet areas, and a laundry room that can be used alternately. On this floor, barrier-free access to the rooms with wheelchairs is possible from the north entrance where vehicle approach and parking is provided. Barrier-free access between the residential floors is provided by an elevator. The staircase window between the floors supports natural ventilation for both floors.

Thoughts that Give Life to Design

We shape our environment, and then our environment shapes us. Pomegranate House is shaped by the thoughts, needs and dreams of its residents. For example, the kitchen is designed with open shelves and cabinets in the light of concepts such as “participation”, “collective labor” and “gender equality”. This way, even someone entering the house for the first time can easily find the tools and equipment they need and participate in the preparation process. The woods used in the kitchen, stairs and bookcase are in harmony and integrity with the structural wooden elements of the house.

However, this is not a claim of “absolute” harmony and integrity. Instead of following a single mold, the building consciously pursues the unity formed by different understandings in daily life. For this reason, the design process started as a conversation of ideas and was carried out by involving the users in the design process.[3]

The approach based on function rather than the search for a purely geometric order can be seen in the window arrangement on the east and west facades, which are positioned and sized according to natural ventilation and lighting.

In his book “Ornament and Crime”, Adolf Loos tells of a rich man’s house designed by an architect from a single mold. Even the place to take off the slippers and put the newspaper is designed. The architect’s art forces the man to make sacrifices and live in harmony with his own home. It does not allow for the flexibility of everyday life. Clothes, household items, everything has to follow the line of the design. Man cannot move as he wishes, he is unhappy. In addition to Adolf Loos’ criticism, the Pomegranate House is not an object independent of its user; on the contrary, it tries to be an architectural reflection of the user’s world of thought, dreams and life. It glorifies function, everyday flexibility, change and even the beauty of imperfections that are part of life.

The pomegranate house does not strive for grandeur and splendor. It follows the human scale to provide a sense of warmth and intimacy even in its largest spaces. Since it is designed to be experience-oriented, photographs and texts will be insufficient to describe the house. Getting to know the users and experiencing the house is perhaps the only real way to describe this house. Getting to know Pomegranate House can also create the feeling of meeting its users.[4]

Why is it called Pomegranate House?

Braudel (1986) says about the Mediterranean: “What is this Mediterranean? Thousand things at once. Not one landscape, but landscapes without number. Not one sea, but a succession of seas. Not one civilization, but a number of civilizations, superimposed one on top of the other.” I would like to continue these words as follows: Both row by row and intertwined. Not one but a thousand times, at the same time. One and a thousand lives.

The pomegranate, which is also Mediterranean, best describes a Mediterranean house that emphasizes the unity of different understandings coming together. The pomegranate is a meaningful metaphor for this house, from its creation with collective labor, to the whole that is formed one by one with the differences of the individuals who will host the house, to the stone weave that comes together one by one like a pomegranate.

Foça and Pomegranate House

Braudel (1986) says that travelling in the Mediterranean is to be astonished by the new appearances of old cities. As a Mediterranean, the same situation is surprising in Foça, which bears the traces of different civilizations and cultures in its layers. It is clear that it has not been very lucky in preserving its historical texture. Disappearing building types and many missing buildings.

Although both floors of the Old Foça houses that have survived to the present are masonry stone, the stereoscopic plates made by the archaeologist Felix Sartiaux in Foça in 1913, 1914 and 1920 show that Foça has structures with masonry stone on the first floor and lath-and-plaster on the upper floor (with or without overhangs) that have not survived to the present . It is also understood from the documentation that all of these mixed stone and lath-and-plaster buildings have mouldings at the floor transition and roof eaves (Bozkır et.al., 2015).

Pomegranate House aims to remind this forgotten architectural type of Foça, which has not survived to the present day. The lower floor is masonry stone and the upper floor is a wooden frame structure. [5]

The first floor of the building, which rises on stone foundation, is masonry stone and supported by wooden pillars. “Foça Stone” (Lithos Phokaikos) used in Pomegranate House is a tuff stone that reflects the local texture specific to Foça and is easy to shape. While using this chemical-free, healthy and long-lasting building material, the facade pattern of historical Foça buildings was taken into consideration in stone arrangement and colour distribution. Similarly, the technique and colours of the joint fillings also refer to the preserved works of Foça. [6]

On the upper floor, timber frame construction technique was used. Inside the plastered white facade appearance, there are layers that provide heat insulation value equivalent to stone walls. The iron railings used on the balcony and terrace corners are interpreted by simplifying with reference to historical buildings.

So, the house which is adapted to the climate also establishes a relationship with the context of Foça.

Zeitgeist and Pomegranate House

Although traditional building materials have been used with reference to the traditional buildings of Foça, the use of these materials with contemporary facilities has enabled Pomegranate House to reflect the period in which it was built. Long spans and large facade windows, which cannot be found in a traditional building, have been realised in this building with the cooperation of stone and laminated timber elements.

The dimensions of the cantilevers, the detached wet areas in the wooden floor of the upper floor and the stone wall construction embedded in the ground are some of the other elements where contemporary details are used. Instead of being monolithic and thick, the wooden pillar at the corner of the staircase located in the main space on the day floor was made transparent by opening it in the form of 4 pieces of pillars and was also used as an ambient lighting element.

The building appears as it is with its structure in terms of material use. Stone and wood appearances are not cladding, but structural as a whole. Stone walls are formed by the arrangement of block stones and are the main carriers of the building. The pine wooden purlins and beams forming the rhythm on the ceilings are the carrier elements of the floor. The traditional texture on the facades of the building is used with the same material and technique in the language of the construction technique based on the material. These structural and structural elements are exhibited with honesty beyond their functions and become a part of the whole that forms the aesthetic perception.

Buğra TETİK Architect (M.Sci+Ph.D.)

References:

- Bozkır, F., Bozkır N. S., Kuyumcu E. (2015). “Foça (İzmir) Sivil Mimarlık Örnekleri Ve Restorasyon”, 5. Tarihi Eserlerin Güçlendirilmesi Ve Geleceğe Güvenle Devredilmesi Sempozyumu, 445-463.

- Braudel, F. (1986). Akdeniz: Mekân, Tarih, Insanlar ve miras = La Méditerranée: Les hommes et l’héritage ; l’espace et l’histoire. (N. Erkurt & A. Derman, Trans.). Metis.

- Felix Sartıaux, Regards Phoceens Le Temoıgnage De Felıx Sartıaux https://journals.openedition.org/ceb/874

- Felix Sartıaux, Phocee 1913-1920 De Felıx Sartıaux, Kallimages, 2012

- Loos, A. (2017). Mimarlık üzerine. (Tümertekin Alp & Ülner Nihat, Trans.). Janus.

Footnote:

↑1 The planning of the houses in the neighbourhood was built within huge retaining walls formed by levelled lands and elevation differences. This was a kind of architecture of fear that also prevented the formation of a regular street and street cross-section that could be walked around the settlement. This situation looked like a dystopian scene in the Mediterranean atmosphere. For Pomegranate House, considering the ecological and economic gains, wall-less planning was preferred by sitting on elevations on the natural terrain. (Back to text ↑1)

↑2 The elevation regime on the land is not to the south, but diagonally to the southwest. I think this is why our neighbours had turned to the southwest. In this location, the orientation suitable for the landscape and climate was south. Although sitting diagonally to the elevation regime without levelling in order to face south requires additional labour during architectural design, the view and energy gain in the period of use of the building is remarkable. (Back to text ↑2)

↑3 I think that detached housing is a type of building where the architect needs to establish more dialogue with the user and be a listener compared to public-use buildings. However; it is possible to transfer the needs and dreams of the residents to the design in different ways. Although presenting the possibilities to the user’s knowledge and preference with their pros and cons requires more effort from the architect, it is a very useful effort to ensure that the users are happy with the result. When designing, it is essential to focus on the user’s memories, daily life and dreams instead of focussing on instrumental elements such as walls, windows and doors. (Back to text ↑3)

↑4 Although there was an alternative approved by the users of the house as a result of the initial studies and design process, I did not want to implement that project. Because during these dialogues and travels, I had the opportunity to get to know the residents of the house better. Mrs Ziynet and Mr Mete one-to-one, and the other inhabitants through Mrs Ziynet’s language like a novelist’s description. At this point, many components such as the texture of Foça, the whispers of the land, our experiences on stone and wood techniques, energy efficiency strategies, the needs of the users, their human characteristics, their world of thought could be handled in a part-whole relationship for me. Although our client approved the plan and massing of the house, I asked him to give us some time to work on a different alternative. Although it may seem that I made a job for myself and wasted time for our employer, if this critical decision had not been made that day, such a satisfactory result would not have emerged for the building users. Because I believe that this last alternative harmonised the design with the needs and life ideas of the residents. After all, as Atilla İlhan said, “…leaps come with accumulated consciousness”. I confirmed this with the happiness I experienced in the last days of 2020, when the house opened its doors, when I saw each user moving in the garden and inside the house exactly as Ziynet Hanım described. Because I saw that the users were happy, that they could be themselves comfortably at home. (Back to text ↑4)

↑5 The design process of Nar Ev started with a meeting in Ankara and the following question posed to us: “Is it possible to build a house that is respectful to nature, responsible and frugal when using resources, without concrete or steel, from earth, stone and wood?” Although respectful to nature, responsible and frugal when using resources is a subject we are experienced in, it would be a new adventure for us to make it completely from stone and wood without concrete and steel. But, of course it was possible. As the subject of a design studio at METU, I had designed a stone house in Antalya’s Ürünlü village, famous for its button houses, and with the courage this gave me, I said that we could do it, but we needed to do some preliminary research. Afterwards, while doing literature studies on stone and wood techniques, we spent time at construction sites where stone and wood applications were made, and we tried to strengthen our acquaintance with these materials. In the meantime, together with a friend of mine who is a restoration expert, we started to carry out the restoration project of the historical Field Marshal Fevzi Çakmak Mansion in Ankara. X-raying the traditional structure was also useful for the new structure.

Mrs Ziynet had heard many times before that such a house could not be built. At first we always heard: “it can’t be done”. Then we took it into our hands and we definitely did it! In fact, these objections had a justified basis. In our country, there was no current regulation for the use of masonry stone and wood together. International regulations, including Eurocode 6 and Canadian specifications, were utilised for the static calculations of the building using a combination of masonry stone and timber frame system. At this point, we worked in coordination and harmony with Ömür Özger, our Static Architect, who we came from the similar culture of METU. I think what brought Ms. Ziynet and me together in the first moment was this: our attitude to strive for the point we want to reach and to produce solutions without getting stuck in memorisations and obstacles. Mr Ömür, as an engineer with exactly the same attitude, was a great fit for the team and took an important responsibility for this project. Nevertheless, the most striking of these stubborn objections was the one after the construction of the building was completed: “No, it cannot be stone and wood! If it were, the municipality would not have given a licence.” (Back to text ↑5)

↑6 During the time we spent in Foça, we closely examined almost every preserved historical stone building. Although Foça has a local architectural identity, the new construction is either completely disconnected from this context or in the form of stone-covered imitations. Although Foçaköy is a new settlement area built on Balaban Hill, separate from the historical coastal area, it was one of our first decisions that the new structure here should be related to the identity of Foça. (Back to text ↑6)